Why We Say They/Them

- Sonal Giani

- Apr 19, 2025

- 4 min read

You might have seen people introducing themselves with pronouns lately—“she/her,” “he/him,” “they/them”—in meetings, email signatures, or Instagram bios. To some, this seems like a small gesture of respect. To others, it might feel confusing or unnecessary. But beneath the surface of these three short words is a much bigger idea—about how language shapes the way we see each other, and how seeing each other differently changes the world we build together.

Language is often invisible to us. We speak it, write it, text it, without thinking too much about how it works. But language isn’t just a tool for describing reality—it actively shapes how we think. The words we have access to, the categories we’re taught, and the labels we use all influence what we notice, what we believe is “normal,” and who we think matters. When the only pronouns available are “he” or “she,” it becomes harder to imagine that anyone could live outside of that binary. And when society can’t imagine someone, it often fails to include, protect, or even acknowledge them.

That’s why the introduction—and in many cases, the revival—of gender-neutral pronouns matters so much. It’s not about adding complexity to language for its own sake. It’s about creating space for people to be recognized more fully. For trans and non-binary people especially, being referred to by the wrong pronoun can be painful. It’s not just a grammatical mistake—it’s a denial of identity, a signal that one’s presence is negotiable or invalid.

This process of updating language to reflect lived reality isn’t new. In fact, history shows us that when words change, society follows. Take the term “sexual harassment.” Until the 1970s, there was no common phrase to describe what women routinely experienced at work—unwanted touching, lewd comments, intimidation. It was Lin Farley who first named it, drawing attention to a widespread problem that had been ignored precisely because it was unnamed. Once the word existed, people could talk about it, push back against it, and change laws to address it.

The same thing happened with the word “intersectionality,” coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw. She used it to explain how race, gender, and other forms of discrimination overlap—especially in the lives of Black women. Without a word for it, these overlapping struggles remained invisible in both policy and public understanding. With a word, a whole new framework emerged—one that reshaped how activists organize and how institutions think about equity.

New words don’t just describe—they allow us to see. They allow us to act.

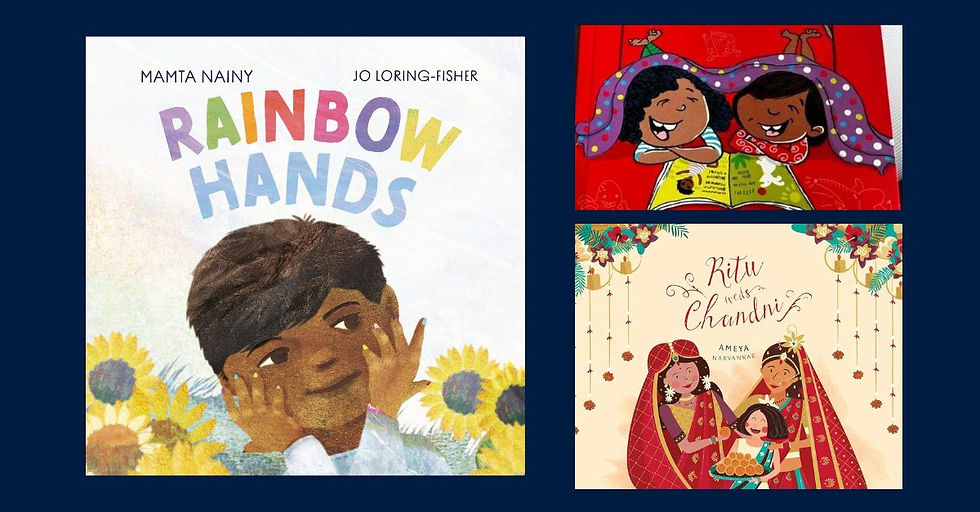

Gender-inclusive pronouns are doing something similar. Words like “they/them,” “ze,” or “hir” give people language for gender identities that have always existed but weren’t always named or respected. Writers like Kate Bornstein and Leslie Feinberg were early pioneers in calling attention to the limits of language—and in pushing English to stretch wider, to hold more kinds of truth.

And English is not alone in this evolution. Many languages around the world have always offered gender-neutral pronouns. In Turkish, the word “o” works for everyone—he, she, or they. Finnish uses “hän.” Spoken Mandarin Chinese uses “tā,” regardless of gender. Even in English, the singular “they” isn’t a new invention. It’s been used for centuries by writers like Shakespeare and Jane Austen when a person’s gender was unknown. The only difference now is that people are choosing it deliberately—to affirm their identities, and to be addressed in a way that feels honest.

Of course, change isn’t always comfortable. Some people resist the use of new pronouns not out of malice, but out of unfamiliarity. They may worry about making mistakes or feel unsure of the “right” thing to say. That’s understandable. Learning takes time. But as with anything worth learning, what matters most is the willingness to try.

There’s also a more forceful kind of pushback—where people frame pronouns as “ideological,” or claim they’re being asked to lie. But that kind of resistance often reveals something deeper: a fear of a world that’s changing, and a discomfort with identities that challenge old categories. In these cases, refusing to use someone’s pronouns becomes a way of refusing to see them at all. And that refusal, repeated over time, becomes a kind of erasure.

This is why the conversation about pronouns is really a conversation about recognition. When we call someone by the name and pronouns they choose, we are saying: I see you, and I respect who you are. It’s a small act, but it opens the door to bigger changes—changes in how classrooms are run, how forms are designed, how policies are written, and how communities are built.

We’ve seen this pattern again and again. Words emerge. New ways of thinking follow. Society expands to include more of us. As linguist Dennis Baron puts it, “Pronouns are about respect, not grammar. And respecting people is always good grammar.” When language evolves, it teaches us to think differently. And when we think differently, we often act differently too—with more curiosity, more empathy, and more care.

So yes, pronouns matter. Because language matters. Because people matter. And because every time we shift how we speak, we’re also shifting what we’re willing to see—and who we’re willing to stand up for.

Comments